As 2025 speeds to a close I, like many other staff in schools, find myself wondering where the time and the year has gone. Working in schools seems to be a constant sprint from the start of a term, until half term, then onwards to the end of term, before a brief pause and go again.

As the year draws to its close it is an important opportunity to stop and reflect so I thought I would share some of my thoughts, the highlights and even some of the low lights from the year with you.

Now for a number of years now I have been sharing pledges, setting out my plans and targets for the year ahead however at the start of 2025 I didn’t do this. I did personally make some notes as to what I would like to achieve and to do however I never packaged this up into the usual blog piece as I would have done in the past. I had been questioning whether having targets led to chasing the targets rather than more broadly experiencing and hopefully enjoying the year, so this may have led me to not put aside the time to create a blog post. I simply deprioritised this particular task. And I think this is something I am struggling with; Having lists and targets, which allow easy measuring of progress and planning, etc, versus being more freeform, having the opportunity to respond to things as they arise, and maybe getting my head up more, to enjoy life, the world and everything. I suspect as always it is about finding the appropriate balance, where I think recent years have moved me more towards lists, spreadsheets (who doesn’t like a todo list with colour coding?) and targets, a little more than I am now comfortable with.

Fitness has been a running theme (did you see what I did there?) for me over the last few years. My distance for the year was just over 250km, which was far less than the 500km and 1000km from previous years, but this year was marked with such inconsistency in my running that even achieving 250km was something to celebrate. I got there in a couple of concerted efforts over a couple of months rather than more evenly across the year. I suspect here it was simply a case of other more important things taking priority and I am happy with that, but it also highlights that I need to see how I can better balance fitness out with other demands, as this year the inconsistency caused me some stress and disappointment. I note that at this point, from a weight point of view, I am heavier than I have been for several years, where weight was a big part of me starting to run, so this is something I am going to have to reflect on ahead of 2026.

Reading has been another thing I have been trying to do more of; Sadly it has been finding the time, however my increasing need to drive around has led me to listen to audiobooks more and more frequently. This has allowed me to get through quite a few books. I don’t think I have engaged with the various titles quite as well as I would have if reading them normally, complete with inserting post-it notes and annotations, but listening to a variety of titles, is definitely far better than doing no reading or listening at all.

2025 has definitely seen me having more time for me, my partner, and our kids. This has been absolutely amazing, however has required me to reduce time spent on other things. Sadly to have more time for one thing we need to have less time for something else; Something I think those leading education at national level could do with remembering. On reflection I wouldn’t have done it any differently. I do however need to get this balance right such that I challenge myself in terms of being busy, yet don’t have unrealistic expectations which leads to stress and disappointment. On the positive side, of particular note is our nice new world map board where 2025 has seen us put a number of pins in the board to indicate places we have been and things we have done. From this point of view 2025 has been an amazing year, with my relationship with my partner going from strength to strength, one amazing memory after another, and the year isn’t even done, with plans for what little remains including a very significant life event, which actually sees me sat here in highland dress, but enough of that for now. We only recently found ourselves flicking through our photo library from events across the year, and we have done so much and had such fun. This all makes me all the more positive and happier as to the looming 2026.

2025 has however saw some less positive moments in some health issues within my immediate family, with these causing some worry and stress. As I write this, one of my elderly family is once again back in hospital having had tests and then a minor surgery. This adds an element of uncertainty, worry and stress to the immediate weeks, and over the festive period, however I hope that the tests and resultant care of the NHS will be able to address things and allow all to enjoy the festive period and progress on a firm footing into the year ahead. I do however see 2026 as involving some difficult discussions as to the future. There is also some uncertainty in relation to my son, who having finished college is still looking for the first steps on the career ladder. I compare his situation to mine, when i was that age, and I think things have only got more difficult for the young. I am sure something will present itself however i recognise how difficult it is when receiving rejection emails or simply not hearing back following applications for junior positions. As to apprenticeships, I feel there are just so many young people chasing the limited number of opportunities, which is a shame as I see apprenticeships as a great way of providing young adults both additional educational opportunities but also the much needed experience of the working world.

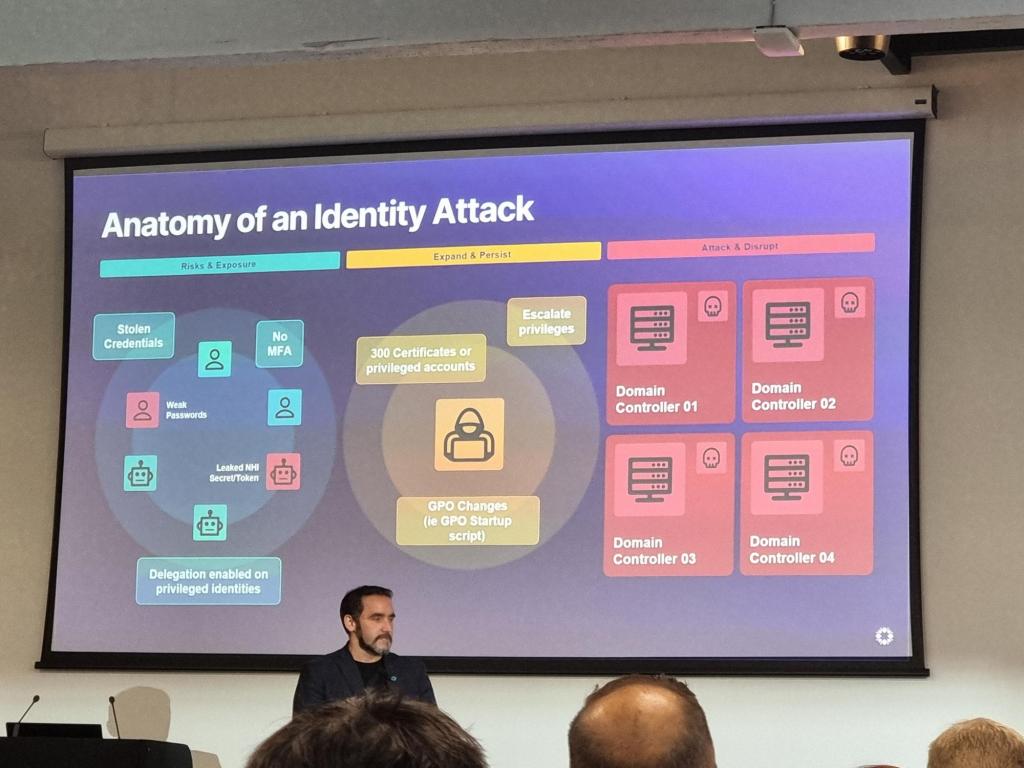

Looking to work and to my involvement in technology and education, it has been a solid year, albeit I don’t think it was as busy as 2024. January saw my first opportunity to speak at the BETT conference, delivering a cyber security session to a packed room, despite a worried period of preparation and fear that my session, last thing on the final day of the conference, would be poorly attended. This year has also seen me awarded the EduFuturists Outstanding IT professional award. The highlight of this, other than the uprising event itself and all of the wonderful people there, was the fact the award was given to me by Dave Leonard, an EdTech superstar and my friend and colleague. Also adding to this event was the fact I also collected an award on behalf of my Millfield colleague Kirsty Nunn. Then there has been my work with the ISC Digital Advisory Group, leading on the 2025 conference, before becoming the new chair of the group, and beginning the planning for next years conference (save the date: June 19th, University of Roehampton, if you are interested! Promises to be an amazing event). And I can’t fail to mention the Digital Futures Group and a WhatsApp group which I often struggle to keep up with. Such a brilliant group of people, doing so many amazing things in schools across the country, while also being open, friendly and supportive people that I feel blessed to consider as close friends. And there is also the ANME, and several hundred WhatsApp groups (thanks Rick 😉) and being able to lead the various Southwest regional events, and some amazing discussions in relation to technology in schools.

Looking forward to 2026, I look forward positively but also am conscious that it likely will represent a year of some challenges and change, but when is this not going to be the case. It would be nice for things to be easy and convenient; however I also note that we need struggle and challenge in order to feel like we have actually achieved something. Some difficulty is actually desirable; it is just about trying to find the right balance. 2025 definitely had some challenges, but looking back it has, in a broad and general view, been successful and positive. I have some amazing memories particularly personally, and I suspect the day ahead of me will see more amazing memories created before 2025 is finished. As I mentioned back at the end of 2024, maybe the journey is more important than the destination, and the journey through 2025 was filled with memories, and a sense of progress. What more can you ask for?