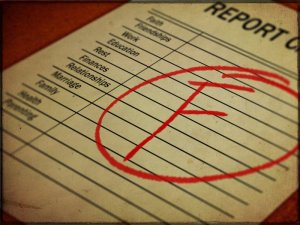

FAIL: First attempt in learning. This for me has always been a great concept, that we often learn the most when things go wrong, however I am increasingly conscious that maybe the world we now live in is becoming increasingly risk averse, meaning that fails are not seen as opportunities to learn, but also that we are actually reducing the number of opportunities for students to learn from difficulties, challenges and even failure.

But why would we want a child to fail?

I suppose this is the key question, who would anyone want a child to fail? I think this almost goes to highlight one of the key challenges in that a fail is seen as a negative conclusion and something we don’t want children to suffer. But what if a fail isn’t a conclusion but is a step within a larger journey? If our fails aren’t terminal or final but are more a road bump along the way, a change to re-channel efforts, to change paths or approaches or to simply learn from error, maybe there isn’t an issue with a child failing.

Desirable difficulty

So, if failing isn’t negative, might it be positive? The concept of desirable difficulty refers to the positive benefits of being challenged rather than finding things easy. Surely something not working or going as we intended, a fail, is definitely a challenge and therefore could represent a desirable difficulty if an eventual positive outcome results. From a fail we have the opportunity to review our practice and identify how we might change to overcome this road bump, and in doing so we learn plus may also grow more resilient. That clearly sounds like a desirable outcome, albeit I will also acknowledge it may not be easy, but I suppose the term “desirable difficulty” already says this.

Risk aversion

The challenge with all this is that, I feel, as a society we are becoming more risk averse. We look at GCSE pass rates and want more students to pass each year, with the pass rates being in the high 90%s. So, this meets our need for all students, or at least most, to achieve, but does it therefore rob students of the opportunities to experience and learn from failure. As teachers we add scaffolding, we differentiate, we provide additional support where needed, and much more to make students succeed, but again are we depriving students of the benefits which result from where things go wrong? In relation to AI in education we worry about AI errors, about bias, etc, where I don’t think we can get rid of these things; Shouldn’t we embrace the technologies, teach students to be critical and accept that sometimes there will be a fail, but that students will then learn from this?

Monitoring and supervision

And looking more broadly we now monitor our children more than ever before, wanting to know their every move and making sure they have a mobile phone on them so they can be easily contactable. We take them to football games and to other events, often being the ones which arrange the events, where once upon a time kids sorted their own entertainment, returning only once the street lights came on. I look at my own childhood and the experiences I had when out with friends, sometimes just playing football or having fun, and sometimes maybe up to things my parents may not have approved of. But in all of this I learned from my experiences, I made mistakes and picked myself up and moved on eventually better for it.

Compliance

And then there’s compliance and the world of health and safety among other areas. We increasingly mandate things or require checks to be carried out, meaning activities we once did now take more time and effort due to the need to deal with compliance requirements. As we add all this extra work and effort, the risk assessments, checks and balances, it makes us less likely to try new things and to experiment. The potential gains of a project, of a new technology for use in the classroom, or many other things may not have changed, but the overhead in terms of checks and balances is now greater than it used to be so this means the perceived differential between the gain and the effort has reduced. This increases the likelihood we will simply evaluate the technology, project or other activity, coming to the conclusion that the benefit is not sufficient to outweigh the efforts needed, and therefore the status quo remains.

Conclusion

I came across a quote recently: “life begins at the edge of your comfort zone”. The challenge however is that we increasingly don’t want to allow students to experience the edge of their comfort zone for fear of fails or discomfort. So what kind of life, and what kind of learning will result?

Not so long ago I read of a discussion in relation to whether the GCSE English Language should be scrapped. Part of the reasoning behind this is identified as being due to the subject identifying a third of students as having failed. As a headline I think it is difficult to disagree with. How can identifying a third of students as having failed be an acceptable thing to do. On reflection my view is that this issue is less about English Language subject and more about the educational system as it is now and as it has been for over one hundred years.

Not so long ago I read of a discussion in relation to whether the GCSE English Language should be scrapped. Part of the reasoning behind this is identified as being due to the subject identifying a third of students as having failed. As a headline I think it is difficult to disagree with. How can identifying a third of students as having failed be an acceptable thing to do. On reflection my view is that this issue is less about English Language subject and more about the educational system as it is now and as it has been for over one hundred years.