As a new academic year begins, this being my 26th academic year (has it been that long??) I just thought I would share some thoughts and maybe predictions.

Artificial intelligence

I don’t see the discussion of artificial intelligence in education going away as there is such potential. The use of AI to support students, to help teachers and rebalance workload and much more. It also makes for a good talking point for conferences or for developments. I have two problems though. One being that I think there will be a lot of talk, especially from vendors, without the reliable evidence supporting the impact and benefit of their tools. As such I feel there will be a lot of misdirection of effort and resources when looking across schools in general. Two is that artificial intelligence is all well and good, but it needs the relevant access to devices, to infrastructure, to support and to trained and confident teachers. These digital divides need to be addressed before schools in general can then seek to use AI and leverage its potential benefits.

Online Exams

The issue of online or digital exams feels partly related to the sudden growth in AI and the resulting potential for AI marking of student work and therefore for AI based marking of student exams. Again, I see this as another talking point for the year ahead but again am not sure we will see much real progress, possibly seeing less progress in this area than in AI. The issue is that exam boards are taking things very tentatively so there first step will be “paper under glass” style exams which simply take the paper version of an exam and digitise it rather than seeking to modify the exam or examination process to benefit from the new digital medium. For me the key benefit of online exams will be realised when they are adaptive in nature so can be taken anywhere and at any time. This then means that schools wouldn’t need access to hundreds of computers for their students to sit an English GCSE exam as the students could sit the exam in batches over the day or over a number of days. This would help towards the digital divides issue as it impacts online exams as schools wouldn’t need as many devices, but they would still need the infrastructure and the support to make digital exams work.

Mobile Phones and Social Media

Oh yes, and then there’s this old chestnut! I suspect the phones and social media discussion will trundle on. Students are being given phones without any parental controls and then schools are having to deal with this. And some schools are taking the prohibition approach which is unlikely to succeed and may just deplete patience and resources. I continue to believe we should be seeking to manage student mobile phones in school, so might restrict use in some areas and at some times but embrace and use them at other times. We need to spend time with students talking about social media and its risks and benefits helping to shape the digital citizens which the world needs.

I also note here that social media is being blamed for the lack of focus and ease of distraction in students, and through association it is the fault of smart phones. The world isn’t that simple, and having recently finished reading Stolen Focus by Johann Hari I am not more aware that other factors such as increasing levels of societal pressure to succeed, increased consumption of processed foods and our on-demand culture are all having an impact on our children. Yes, social media, and by extension smart phones are playing their part but they are not the root and sole cause of the issues in relation to attention which we are seeing in schools and more broadly with children.

Fake news and deepfakes

This links to AI and also to mobile phones and social media, in the increasing ease with which fake news content can be convincingly developed including the use of images and video, and then shared online. As fake news becomes an increasing issue, which I suspect the US elections will draw some focus on, there will be an increasing need for schools to consider how they discuss and address this challenge with their students. More locally within education and within schools will be where we start to see increasing use of AI tools to create “deepfakes” by students and involving other fellow students, either “just having a laugh” or for the purposes of bullying. This will be very challenging as the sharing of such content will quickly stretch beyond the perimeter of schools, spread through social media, messaging apps and the like, but where the victim and likely the perpetrators will be within the school.

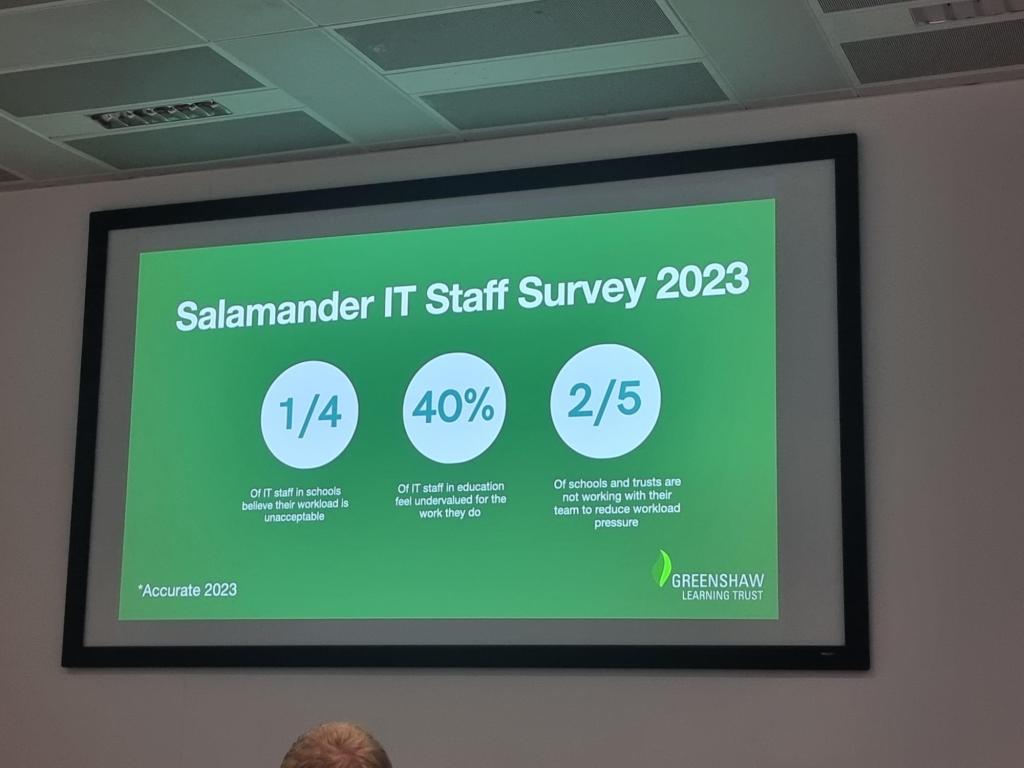

Wellbeing

This one came to me last, but if I was re-writing this I would likely put it first. We talk about wellbeing very much but every year we look to see if the exam grades have gone up and are faced with increasingly compliance requirements around safeguarding or attendance or many other areas. Improvements in results, or even the efforts to improve results mean more work, which means more effort and more stress. More compliance hoops equally mean more effort and more work. So how can we address wellbeing if educators are constantly being asked to do more than they did previously. And exam results and compliance are just two possible examples of the “do more” culture which pervades society possibly driven by the need for economic and other growth as something to aim for. Although growth and improvement is something laudable to seek, it cannot be continuous over time, not without deploying additional resources both in terms of money and human resources. As such there needs to be a logical conclusion to the “do more” culture and my preference would be for us to decide and manage this rather than for it to happen to us. AI can help with workload for example giving more time for wellbeing however my concern here is that this frees up some time to simply do more stuff, albeit stuff which might have an impact, but not positively on wellbeing.

Conclusion

The above are just five areas I see being cornerstones of educational discussion in the academic year ahead. I suspect other things will arise such as equity of opportunity, although I note this links to pretty much all of the above. There will also be other themes which arise but it will be interesting to see how these particular five themes develop during the course of 2024/25.

And so with that let me wish everyone a successful academic year. Let the fun begin!